Dayton Daily News

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Seeking Solutions

Ideas People: A Conversation with Bill Kennedy

Why would I need to go to Egypt when there are more than 5,000 prehistoric sites recorded within 25 miles of Dayton? –Bill Kennedy, Curator of Anthropology, Boonshoft Museum of Discovery

The Boonshoft Museum of Discovery has a lot of great stories to tell, as any visitor knows. The man in charge of preserving and telling the ones that have to do with the ancient history of our region is Bill Kennedy, the museum’s curator of anthropology. We talked to him recently about his job, and what we can learn from our past.

Q: What does an anthropologist do?

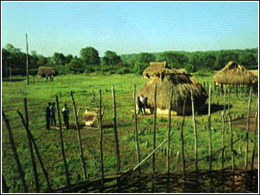

A: I work for the Dayton Society of Natural History, which operates three museums: the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery, SunWatch Indian Village/Archaeological Park and the museum at Fort Ancient State Memorial in Warren County. Anthropology is the study of people with the goal of understanding how and why cultures change.

I’m an archaeologist by training, which is a sub-discipline of anthropology. As a museum curator, I am responsible for the care of a 1.4 million item collection of anthropological and archaeological objects from around the world, but I have other duties as well. I conduct research, excavate and reconstruct archaeological sites, present exhibits and programming, and teach college-level courses. Most of what I study is prehistoric (meaning “before written history”) Native American culture.

I’m an archaeologist by training, which is a sub-discipline of anthropology. As a museum curator, I am responsible for the care of a 1.4 million item collection of anthropological and archaeological objects from around the world, but I have other duties as well. I conduct research, excavate and reconstruct archaeological sites, present exhibits and programming, and teach college-level courses. Most of what I study is prehistoric (meaning “before written history”) Native American culture.

Q: What drew you to the field?

A: Many people who become archaeologists grow up with a love of ancient Egypt of medieval Europe, but I was fascinated with local history: Tecumseh, Simon Kenton and Daniel Boone. That interest began within Boy Scouting, which is where I met Howard Clippinger, who became a surrogate grandfather and was a collector of Bronze Age artifacts. I would listen to him talk for hours about doing archaeology with the WPA during the Depression, and it inspired me.

As an undergrad, I worked as a zookeeper at what was then called the Dayton Museum of Natural History and through that connection I was able to excavate with the museum for a summer. The excitement of that initial experience with J. Heilman and Lynn Hanson, the curators of anthropology at that time, convinced me that I wanted become a professional archaeologist.

I majored in anthropology at Wright State under Bob Riordan and continued into graduate school. It was the encouragement of these early mentors that put me on the path and kept me on it. Now the positions are reversed and I’m the one doing the encouraging, which is the most meaningful part of my job.

I majored in anthropology at Wright State under Bob Riordan and continued into graduate school. It was the encouragement of these early mentors that put me on the path and kept me on it. Now the positions are reversed and I’m the one doing the encouraging, which is the most meaningful part of my job.

Q: Do you think people know enough about your field? How do you try to make them ore aware of our early history?

A: Most people think I dig up dinosaurs, which I don’t (that’s paleontology). If people do know what archaeology is, they usually ask me if I’ve been to Egypt yet. (Nope.) Most people don’t realize that the archaeological record of our area is long, dense and fascinating. People have been living in Ohio for at least 11,000 years with the earliest arriving during the Ice Age. The Hopewell people are known around the world for the large earth-works they built here, even though most Ohioans are unaware of them. The Fort Ancient earthwork alone encloses over 100 acres with three and a half miles of earthen walls. American archaeology as a serious discipline began with scholars pondering the question of who built these mysterious earthworks. Why would I need to go to Egypt when there are more than 5,000 prehistoric sites recorded within 25 miles of Dayton?

Q: What do you like best about living and working in Dayton?

A: There are lots of advantages, such as a lower cost of living, affordable housing, and short commutes, but it’s the intangible benefits that are the most important.

My wife and I have lived in South Park Historic District for over 10 years and we’ve chosen to raise our two girls here. Most people think you move to a historic district because you like old houses, but architecture doesn’t make a community. The most important ingredient that makes a good neighborhood is good neighbors, of which we have plenty. People who move into our neighborhood usually do it against the advice of the non-city dwelling friends and family. When they get there, they discover that they’ve found what they didn’t know they were looking for: a community of people who wnt to be part of something bigger than themselves.

Q: What are your hopes and expectations for the area’s future?

A: I see a hopeful and positive future for the area. I hope that the region is going to grow in terms of population or employment in the short term, but I think we can at least grow in terms of our quality of life. Hard times force us to prioritize and focus on what’s important, like a sense of community pride.

This is a great town. We have the benefits of being big enough to offer the cultural benefits of a large city like a great park system, theater, museums, shopping restaurants and entertainment. We also have the benefits of still being a small town at heart with hard-working people who share common values.

The City of Dayton has an image problem, but I don’t think we solve that problem with better marketing. Marketing is how we bring people who don’t already live in the area. What we need is to stop competing with ourselves—to think and act as one large community with price in our core city. It’s ultimately up to individuals, because people see what they choose to see. It doesn’t matter how good or bad a place is if people don’t perceive it as good. Cynicism is for cowards.

Q: What do you think we can learn from our past?

A: The past only exists in the things we say about it, yet it has an incredibly powerful impact on our perceptions and actions in the present. History is virtues first line of defense, but it can just as easily be perverted. Nazi Germany and Communist China are the obvious examples of regimes that have misused history and archaeology on a large scale as incredibly powerful propaganda tools.

History matters. Symbols matter. Every day, people around the world kill and give their lives for what they believe about the past. If we choose to ignore history or fail to question how we know what we think we know, other people will be more than happy to create a narrative to suit their own agenda.

The challenge of history is to comprehend that the past isn’t static. What’s happened has already happened, of course, but how we understand it is always changing. True history is dynamic, and the only time it’s simple is where it’s completely wrong. History is the search for perspective and knowledge.